You dropped art for two years after studying at art school and before starting your side project. When did you feel your hobby became a full-blown occupation?

I studied Visual Communication (basically Graphic Design) at Stellenbosch University. It was a very rigorous course, and quite demoralizing. A number of us (in my class specifically) didn't walk away with the confidence to enter into creative fields. I was mostly critiqued for my sentimentality; the fact that my work was always kind of nostalgic or sentimental. They kept trying to push us into a more conceptual route. The irony is that there’s this narrative of the art world being so open and progressive, but it felt to me like we were all being pushed in the same direction. It took me a long time to realise that the things that I was most heavily critiqued for were actually my strengths, and that there was an audience out there who would appreciate that kind of work. I think that's a really important thing for people to realise: what makes you weird or different is sometimes where your magic lies.

I was quite dejected after that and really didn't want to paint ever again, actually. Then when I met my husband, quite early on in our relationship, I showed him some of my old work. And he said, oh, you should really draw again, you know?

He gave me a drawing book, and encouraged me to draw just one picture. So I drew a picture of us, the two of us sitting in a tree (because on our first date we ended up climbing this beautiful old tree, strangely). It encouraged me to dig up my old work and start giving it away to friends, which is when a gallery owner saw one of my pieces in a mutual friend’s home and approached me for a group show. It all kind of snowballed from there, but it took a while for art to become my full-time career. When I started the project, I had about 12 different jobs and I was just working myself to death.

Is this the ‘Paintings for Ants 365’ project?

Yes, I started it in 2013, when I decided to try and paint a miniature every day. The idea was that I would still be able to do the jobs that were earning the money to sustain me but I would do this little thing for myself for an hour every day. And as the year progressed people started catching on, booking dates and you know, people could book their birthdays, wedding days and make suggestions for the subject matter. I remember the way I priced my work, I literally looked at my monthly budget and what I needed to cover rent, bills and food and then I divided that number by 30. So that was what each original piece cost.

The cool thing about it is that it ended up being really affordable and accessible for people, and the entire 365 pieces sold out before the collection was even complete. The other thing was that as people were booking work, I was able to start quitting my other jobs. The first job I had was as a PA for an events company and it was probably the worst position I could have ever put myself in because I can hardly even organise my own life. The company started to go under and I was approached to take a voluntary retrenchment. I had to sit back and ask myself what I was doing in the job and I realised that I was doing it for the salary, and that didn’t feel like a good way to be spending my life. So I took the voluntary retrenchment. I had no idea what I was going to do, but I had waitressed before. So I kind of just thought, you know, if I have to just waitress and figure things out, I'll do it. So I kind of got into this mind space of just saying yes to everything. I just thought, I have no idea what I'm going to do or what I want to do. So how can I say no to things?

I never imagined that I would end up being an artist and I don't know if that's because I didn't want to be or because I didn't think I could be. I think it's got more to do with the narrative that I had in my head of what an artist is and what that looks like. And I wasn’t that.

I met this French guy who bought this very old dilapidated hotel, which we called the crack house. It was in a pretty bad state and there were blood stains on the floor, no working toilets or lights or anything. But he said, look, if you want to use one of these rooms as your studio you can do that in exchange for a painting. So I said okay, and for the next three months, I worked in the space and I would basically just work until I needed to use the toilet and then I’d have to go home.

Atang Tshikare was working in the space next door and he was hustling, just like me, and he told me about this bicycle customisation project he was working on, airbrushing bikes. I was like, cool, I guess I'll do that too, you know? Then a woman asked me to proofread her wedding magazine. I ended up putting together articles for this wedding magazine and proofreading it. Then a jewelry designer asked if I could make tiny paintings - she wanted to make pendants and put paintings in them. So I started doing that, and I was just churning these pieces out and she would put them in pendants and then sell them as wearable art. I also started going to castings, being in advertisements, for whiskey or whatever, and being the girl drinking at the bar. Anyway, I guess the moment that art became a full-time job was when I quit the last of the 12 other jobs and I was making enough money just through my art. It was a process, but I got there in the end.

How long was this period of you having 12 jobs?

It was a year. My best friend Ashleigh (who has now started a company called “Artist Admin” with my husband, and manages the admin for artists like me), said to me, you’re working yourself to death, but you're still not making enough money to survive. She suggested this course for artists and said to see where it takes me. It was a three-month course at the UCT Graduate School of Business called Business Acumen for Artists. They gave us an introduction to building a brand, negotiating, having an online presence, how to charge for your work, you know, the basics. So I did that, and it was just mind-blowing to think that we hadn’t learnt any of that in 4 years at University.

The implication is that studying art at University actually just primes artists for signing with a gallery. Which is fine - there’s a place for it - but is it really the only way? A model where a gallery takes 50% of everything you earn, for the rest of your time with them, even though you’re paying for materials and framing and, you know, putting in all those hours - that model just doesn’t work for everyone. So that course really reframed the way I thought about things and encouraged me to pick one thing, try it for a year and see how it goes. That’s what sparked the idea to try and do something every day for a year. And I thought, well, what if I painted a tiny thing every day, I could finish it in an hour and then I could have a whole collection by the end of the year (and maybe even have a solo exhibition!).

So I guess your time over this year inspired the ‘365 paintings for ants’. Was there any other inspiration behind this?

I was 13 when my first brother died, and I was 21 when the younger one died. So I think the idea of dates and sentimentality was deeply ingrained in me. It created this compulsion for me to process a bit of the guilt that I was feeling that I got to be alive and I got to experience life by marking every day. In a way, that project was a way for me to make tangible that I was living. You know, I was doing it every day. It was a bit of catharsis and then it slowly morphed into more of a celebration, a practice of gratitude, rather than something I felt like I had to do.

We're huge fans of poet and activist Amanda Gorman in our studio. We saw you created a miniature portrait of her as part of your Ants collection, what was your creative process with this?

That moment at the inauguration was just such a profound moment. Coming off the back of Black Lives Matter, #MeToo movement and feminism and all of the things that we've been dealing with. Also getting so close to having a female president in America, and that not happening, you're always kind of on the edge and just not making that switch.

I think the moment that she stepped out there and read that beautiful poem was such a profound moment for so many people. I felt compelled to celebrate and commemorate that in my own way.

Has gender ever influenced your art, especially as your works are grounded in sentimentality and sensitivity to your surroundings?

I think sentimentality and connection to nature are not exclusively feminine qualities. I think that those are qualities that we need a lot more of in the world right now. If we look at what's happening with wars, and this very aggressive, domineering energy, we could do with a lot more kind of mindful presence in the world, connection to nature and making more decisions in positions of power that are going to positively affect our planet and its people. If my work could in some small way help people reconnect with that side of themselves, that would be more than I could ever ask for.

What does an empowering role model in the art landscape look like to you?

I think artists who model openness, honesty and vulnerability are inspiring to me. I appreciate the artists who are trying to break through this kind of elitist vibe that there is around the art world, and to make it more accessible. It’s disturbing to see how the industry really works, how exclusive the art world really is, and how few people actually have access to art in their homes. The system has become very broken. I think there's an opportunity for artists who are independent, to kind of pave a new way to see how we can do things differently.

What are your expectations for the future of your art and what advice would you give to women who want to enter the art landscape?

For my own work, all of this has been such a gift. It was not something that I ever anticipated or expected in any way. So honestly, just as things are unfolding, I'm constantly surprised and delighted by what is happening and how many people support my work. Having success and people supporting me has opened up the possibility for me to dream about, you know, different ideas. And I always have a few pretty ambitious ideas lined up. I’m working on a really exciting project right now to do with marbles. It came about when the pandemic hit, and my son was four years old. I was watching him experience the world in such a heavy way and thought back on my childhood and how marbles symbolize that really playful, no stakes, kind of childlike, fun and innocence.

But in terms of my plans for the future, I'll paint for as long as my eyes allow it.

In terms of women who want to enter the art landscape, that's a tough one. Because it's hard. It's not easy. And I have it a lot easier than a lot of people because I have so much support. The main thing I would say is to try not to have too much financial pressure on yourself right off the bat. If you are able to keep a job or a stream of income, that'll take care of the bills so that that pressure is not on your work, then that's first prize. Do a business course aimed at artists, a very practical kind of hands-on business course. Get a company like the one I use to do your admin for you (admin completely consumed me in the first kind of two years). I would spend eight hours a day painting and then spend another three hours just corresponding with people wanting to book paintings and shipping things and tracking things. Eventually, I just spent all my time on admin and not really making art. So if you have any money to put towards someone doing that for you, even if you have to build it into your shipping costs, or add a little bit onto your art prices, then definitely try to get as much admin out of your world as you can.

I feel like this has been said so much, but you have to put your work out there. I think that's what the 365 projects forced me to do. I'm a perfectionist, and I was a serial not-finishing-paintings-person, I just felt like none of my work was ever completely done. I never wanted to share them, because they weren't ready. Having that daily deadline forced me to put stuff out into the world that I would never have signed off on before. And sometimes I would find that those were the pieces that people resonated with more than anything else. It broke that thing in me that you need to hide your work and make it perfect before you put it out into the world. Make it interactive, make it a conversation rather than this presentation of a “perfect” complete thing. So put your work out there. That's the only way you get seen.

––––––––––––––––––––––

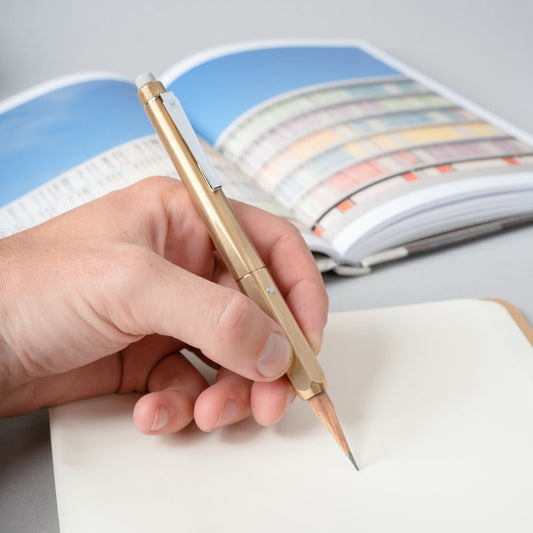

It was such a pleasure speaking with Lorraine Loots, the creator of "365 Paintings for Ants." Her empowering story is one of hardship and success. The Makers Cabinet team felt empathetic of her journey, having studied product design – a pipeline traditionally designed to prepare burgeoning makers for a very specific field, needing to search elsewhere for the skills and knowledge needed to create a livelihood of our own, in our own vision.

Explore the rest of Lorraine's works on her website lorraineloots.com